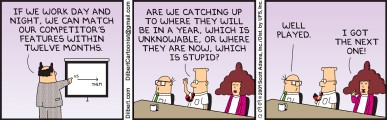

There are dozens of Dilbert cartoons that make fun of the sales guy. In Dilbert’s world, the logical engineer is king while the salespeople — and frankly all the other business people — are dolts.

The transition from being an R&D and product development company to a sales- and marketing-driven company is often a bumpy one for founders. The technically-minded people — who lead most of the high-tech companies we work with at Ben Franklin — often do not get very excited about making sales calls. In fact, many founders have very little understanding and respect for the sales process. They reveal themselves through comments like, “We’ll just find a business guy,” or “We’ll sell it through distributors,” as if they could just as easily hire a monkey to do sales.

We see it over and over again. Did you ever notice that there is no sales course or sales major in MBA programs? Yet our experience tells us that having an ability to sell is at least as important to success as the ability to develop new products.

Many of our tech founders confuse the existence of a market with the existence of demand. This confusion leads many entrepreneurs to read a Gartner market study and declare that they will be a success by capturing just 1 percent of the market. They assume that by developing a new formula or device, a small market capture percentage will just naturally be theirs. That assumption might be exacerbated if they worked for a large corporation: In the case of a Cisco or SAP or Siemens or any Fortune 5000 company, the difficulty of obtaining customers is distorted by brand. A large part of creating the demand for a product is already finished when a salesperson mentions who they work for.

When I notice this phenomenon, I draw on my inner Zen and say, “Grasshopper. Markets exist. Demand is created.” Many of the best products and services were developed and sold by first understanding individual customers. When you find two — and hopefully more — customers who share characteristics and needs, then you’ve discovered a market. It’s important at this point to realize that you haven’t “created” the market; you’ve “discovered” it.

Many Dilbert disciples cannot grasp the idea that a successful salesperson has a fundamentally different personality and skill set than a technology founder. In a startup fighting for its first customers, these talents are essential.

- Good salespeople listen first and speak about their product after they have heard the customer talk about their problems.

- Good salespeople understand that customers are busy. They will follow up consistently and politely. Technology-first founders are often accustomed to being the teacher — they might even be a professor or MD — so why should they follow up if the customer didn’t understand them the first time?

- Good startup salespeople seek ways of remaining involved with their prospects to identify solutions to future business problems, even if it isn’t with their company’s product.

- Good salespeople know what metrics to track for their business’ sales goals and understand how to manage and interpret the pipeline of sales prospects.

Do not live in Dilbert’s world. If you’re building a technology company and have spent most of your life developing advanced technological products — or managing teams of people doing so — but have spent little time in the presence of your prospective customers, seek the best possible sales force you can. If you do not, you’re likely to end up with an expensive hobby rather than a successful venture.

Lesson #1: There Are No Lessons.

Lesson #1: There Are No Lessons.

Every Business is an “L” Business

Ain’t talking ’bout love.

Ah, the “L” word.

No, not “love”. The other “L” word.

You know the one…the one that puts startup founders into an internal rage. The one that signals to the founder that the person using the word finds their business less than exciting. When someone refers to the founder’s business as an “L” business, it usually means that someone thinks it will be a slow-growing, part-time, hammock-lying, uninteresting venture with no hope of any sort of financial exit. The word should be only discreetly uttered aloud in reference to a business, so please read the following silently to yourself: Luh….luh…Lifestyle!

Oh, the defamation! The slander! The shame of it!!

This post is to help those of you who’ve been labeled with the “lifestyle business” tag and felt dissed and offended, recover from the trauma. Hopefully, by talking about the issue of “lifestyle businesses” I can help those who’ve been accused of such a suggestion to understand the origins of the phrase, accept that it may be true and move on with the knowledge that every business reflects the founders lifestyle.

TechonomicMan’s First Observation: Is it actually true? Usually, the “lifestyle business” tag gets used by professional investors…VC’s and angels…who do not believe your business plan warrants significant equity investment. There are lots of reasons why investors won’t make equity investments in companies and the founder who exhibits a history or a plan that comes off as complacent and light on the drive needed to produce returns an equity investor needs, may get the “L” tag. Examples of businesses that may get the “L” tag due to the founder include the majority of tenured professors and medical doctors who launch new ventures. These are VERY difficult, lucrative and, in most cases, irrational professions to walk away from to launch a tech startup. Successful consultants in their field are another example of founders who, without just the right set of other circumstances, often get accused of lifestyleness. Guess why? Because it is so often true! These founders are often trying to fit the launch of the company into their professional lifestyle!! We appreciate that you give up your evenings and weekends and vacation days to work on your venture…but that makes it a hobby. And professional equity investors need to know that everything else professionally is zeroed-out and the business you’re asking us to back is the 24/7 obsession it needs to be.

Complacency is the other “lifestyle” give away. “Well, we had trouble solving a technical issue on the product and my technical guy had to spend time fixing some things with a prior consulting gig he had and so I had to call someone who hasn’t gotten back to me for 2 weeks…etc., etc., etc.” is a sign that fixing the technical bottleneck was not the most important thing in your life. And complacency can be seen a mile away by experienced investors.

So before getting indignant about being accused of appearing to be a lifestyle business, understand that while you may be the exception to the investor’s experience with lifestyle businesses…you’d indeed be the exception.

TechonomicMan’s Second Observation: Some great companies are lifestyle businesses. Ok. so you suspect the equity investor has tagged you with the “L” business word. Have you stopped to think about what is so tragic about that? One of Ben Franklin Techonology Partners most successful companies was a lifestyle business…currently with about 4,000 employees, almost entirely owned by the “lifestyle” business founder. Oh, woe is him! If you exhibit the kinds of issues that a typical “lifestyle” founder exhibits, and equity investors decline your pitch, you absolutely, positively can still build a hugely successful business. As big as you want. Think Yuengling Beer…still family owned, not parsed out in preferences to a bunch of venture capitalists… and after >150 years, the 3rd biggest beer maker in the US. Without that outside equity, I will concede, you’re gonna need a few more pinches of luck along the way. But with a little luck, you could have both a nice business and a lifestyle of answering to yourself instead of an exit-driven group of investors.

TechonomicMan’s Third Observation: It turns out that every business is a lifestyle business. This is my overall point with regard to the Lifestyle Business moniker. Know who you are as a person before you decide who to be as a business. (I’d like you to read that last sentence again for emphasis, because I think it is a good one.) If you plan to attack a market segment dominated by one or more of the planet’s Fortune 5000 companies, you’d better be 1) able to commit 24/7 to the company and 2) capable of delivering Fortune 5000 success. Do not lie to yourself or to others. Do not rationalize that you’ll be the exception…you need too much luck for that. Be in the right place in life before you try to start a growth-oriented startup. Your business is going to DOMINATE major time-chunks of your life and your lifestyle will not be the same afterward. Add some employees who have families that depend on the success of you and your business and, well, you’ve got yourself a life-consuming obligation and therefore, a lifestyle business with 2 employees…or 4,000.

So I’d start with the end game in mind. The business you build had better fit the lifestyle you expect to have. And vice versa.

Share this: